This article will provide you with a framework for deciding whether you should create an index for your database query or not.

Motivation

Anecdotally, I’ve seen team members contemplate “whether it’s worth it” to create an index for a new database query they have written. Often they are concerned that the table size is too small to justify it.

By the end of this article, you will be equipped with the tools you need to confidently decide when to index your database tables. You will no longer share the same anxiety as Prince Hamlet who is still left asking: “to index or not to index?”

Assumed knowledge

This article will assume that you have a basic understanding of Postgres database indexes. If not, you can read here. If you don’t want to read Postgres documentation, you can stop reading now and carry on with your life!

For everyone else, let’s go on this journey together.

Trade-offs

As with every decision in software engineering, there are always trade-offs. Let’s go through some of the major pros and cons of introducing a database index into your table.

Most of this article will relate to the B-Tree index which is the most common type of index in Postgres. We will also be assuming that your application reads more than it writes, which is true for most applications.

Con: Storage costs

To create an index, it needs to be stored somewhere.

A B-Tree index is essentially a mapping between index values and the tuples containing these values. As such, the storage cost of an index scales linearly with each row in the table (approximately).

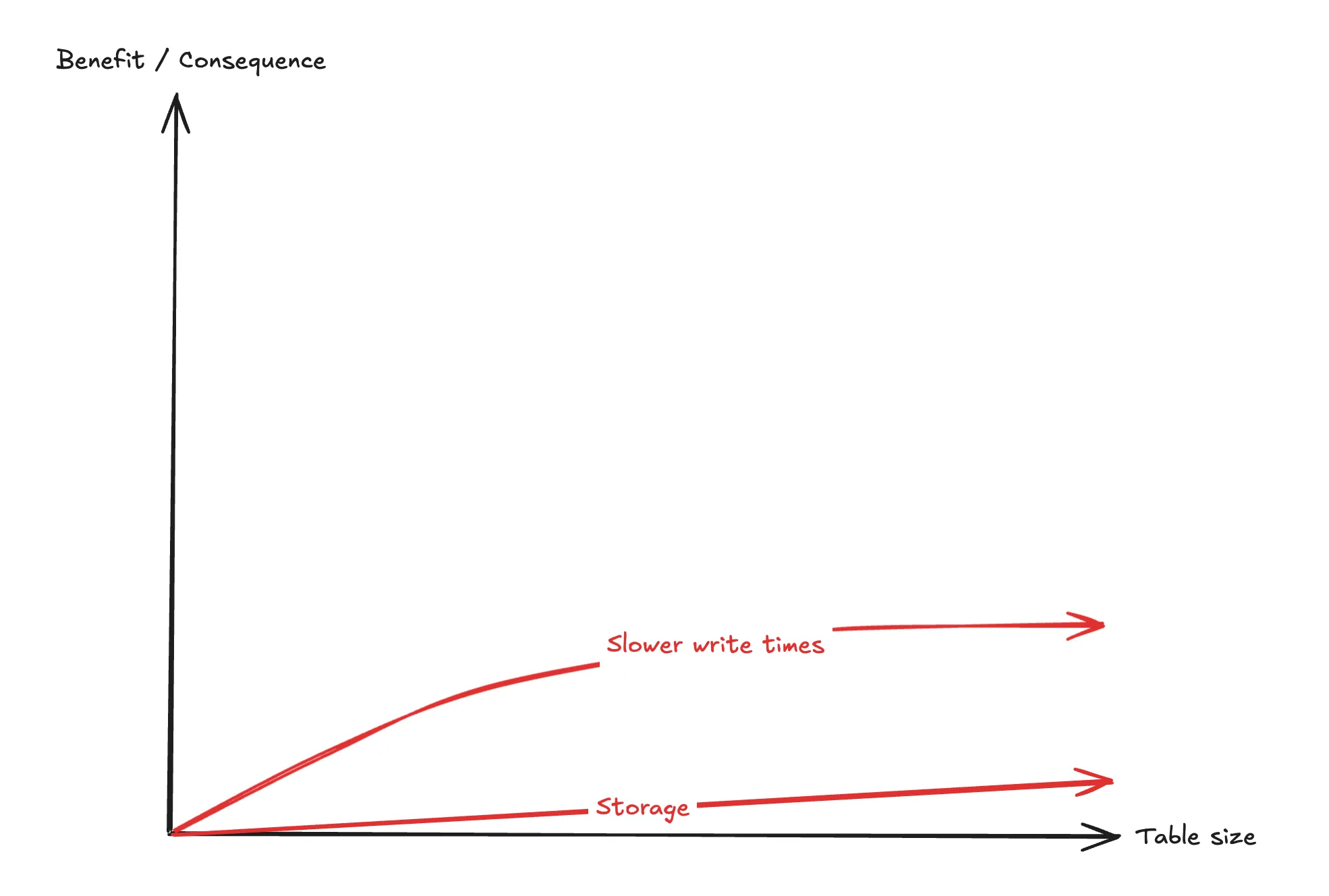

Con: Increased write latency

Once an index exists on a table, it means each row being written takes a little bit longer as the index needs to be updated.

A B-Tree index is essentially a balanced, multi-way search tree meaning the insertion cost scales logarithmically with each row in the table.

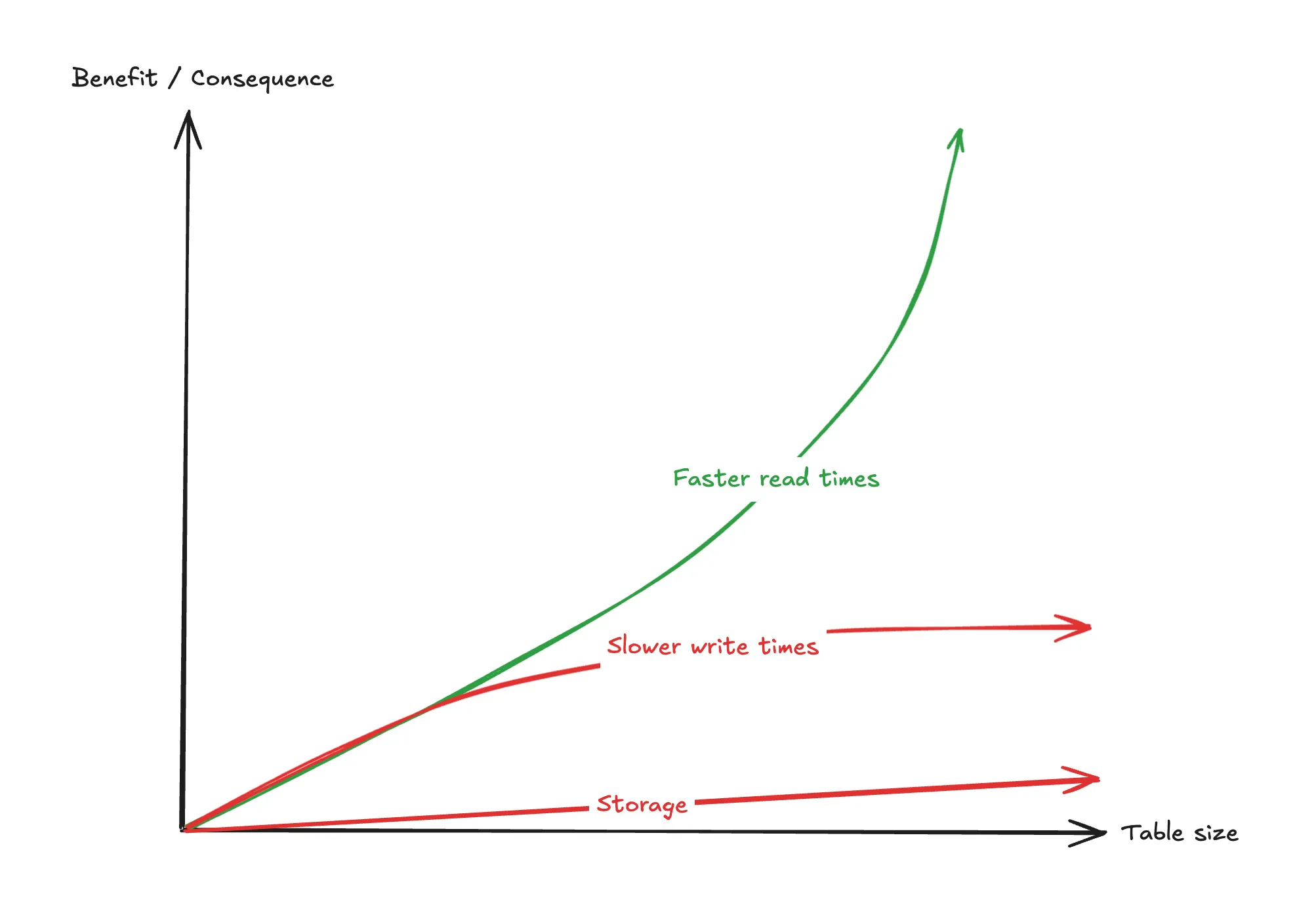

Pro: Lower read latency

This is why you even bother introducing an index - it dramatically speeds up read latencies across a table when querying by that column.

Rather than scanning the entire table sequentially, Postgres can traverse the index in logarithmic time using a B-tree lookup. So the lookup time is asymptotically much faster.

The below table compares the number of operations in a linear scan versus a logarithmic index lookup at various numbers of rows.

| Rows | Without index | With index | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 | 500 | 10 | 2% |

| 100,000 | 50,000 | 17 | 0.034% |

| 1 mil | 500,000 | 20 | 0.004% |

| 100 mil | 50 mil | 27 | 0.000054% |

As your table grows to ~100K, you can see that value of an index starts to become significant. Even at 1,000 rows the lookup cost with an index is 2% compared to without.

In practice

The above table is just a comparison on the number of operations between the 2 search algorithms, it is not exactly indicative of what Postgres does in practice. In reality, factors such as caching, concurrent operations, compute resources and I/O constraints all impact the speed of your database queries.

This comparison serves to conceptualise the benefit of an index when compared to sequential scans with some ballpark comparison points.

If you are interested in understanding the actual performance benefits of an index on your own database, use EXPLAIN ANALYZE.

The framework

Claim: For all sizes of a table, the pros of an index outweigh the cons.

The benefit from reduced read latencies grows much faster than the costs as table size increases. Even at small table sizes of ~1K the performance benefit is noticeable.

Yes there are table sizes so small that the query planner won’t even use an index and will opt into a sequential scan, so your index is effectively unused. In these cases however, the negatives of having this index are so small that they can be considered negligible. And now you’re prepared when or if your table reaches that certain size.

Default to indexing

The recommended framework to follow is to always introduce an index, unless there is a clear reason not to.

Clear reasons not to index

Here is a quick list of clear reasons not to index. These are exceptions to the rule:

- The column has extremely low selectivity.

- The write to read ratio is extremely high (event or log tables).

- Analytical queries where bitmap scans dominate.

- The table is temporary.

Maintenance

This approach does introduce an additional difficulty in that you have to maintain these indexes. Access patterns to your database can frequently change and that means your indexes will need to change with it.

I find this is not that difficult if you live close to your database and have well designed schemas that suit your product’s access patterns.

There are also some tools that can assist you with this.

PgHero

PgHero is a great tool for Postgres database health. There is a section on unused and duplicated indexes which can help you identify wasted indexes that only serve to slow down writes and waste storage.

No ORM

The no-orm framework actually enforces that you write an index on a column before you can query that table by that column.

Yes this framework was written by me.

Know your application

Of course, this framework is opinionated and makes a lot of assumptions about your application and how it works. I believe this framework can be applied in most cases, but as always there might be some nuance in your application where this framework isn’t useful.

You’re the expert on your application. At the very least, hopefully this article helped you understand some fundamental trade-offs of indexes which you can apply to your own application.